Proof vs truth

There are now two distinct categories of validity of a logical statement.

- Can we find a (natural deduction) proof $X \vdash Y$?

- For any truth assignment that makes $X \mapsto T$, must $Y \mapsto T$?

Finding a proof is an explicit set of moves to go from $X$ to $Y$ while truth assignments are somewhat external to $X$ and $Y$ but it turns out that the these two notion are closely related.

As such we will given the second notion some notation, we will write $X \models Y$ if for any truth assignment whenever $X \mapsto T$ then $Y \mapsto T$ also.

We can check this via a truth table.

Example. Let’s take \(X = (A \to B) \land A \ , \ Y = B\)

Then we have

| $A$ | $B$ | $(A \to B) \land A$ |

|---|---|---|

| $T$ | $T$ | $T$ |

| $T$ | $F$ | $F$ |

| $F$ | $T$ | $T$ |

| $F$ | $F$ | $F$ |

and can see that when $B$ is true so is $(A \to B) \land A$. So \((A \to B) \land A \models B\)

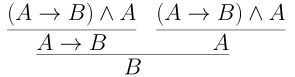

But, we also know that \((A \to B) \land A \vdash B\) from the proof

The proof above is very close to $\to$ elimination. Indeed, that is the last set. It is easy to see that \((A \to B), A \models B\)

This means that whenever we apply $\to$ elimination, we also have $\models$ at that step in the proof. We come to our first real mathematical theorem.

Theorem. Let $X_1,\ldots,X_r$ and $Y_1,\ldots,Y_s$ be collections of formulas in proposition logic. If we know that \(X_1, \ldots, X_r \vdash Y_1, \ldots, Y_s\) then \(X_1, \ldots, X_r \models Y_1, \ldots, Y_s\)

With the example above and the accompanying discussion, this might not be so surprising. A natural deduction proof is built from the elimination and introduction rules listed in the previous sections. One just needs to check that all of these rules don’t break $\models$.

At the moment, we content ourselves with this sketch of a proof. It should be enough to leaving your favoring the validity of the theorem but it falls short of a full mathematical proof.

This theorem goes by the name of soundness of propositional logic.

But, wait, there is more.

Theorem. Let $X_1,\ldots,X_r$ and $Y_1,\ldots,Y_s$ be collections of formulas in proposition logic. If we know that \(X_1, \ldots, X_r \models Y_1, \ldots, Y_s\) then \(X_1, \ldots, X_r \vdash Y_1, \ldots, Y_s\)

In fact, you can somehow conjure a proof from the aether just from knowing whenever $X_1,\ldots,X_r$ get assigned $T$, then so does $Y_1,\ldots,Y_s$. This is usually called the completeness of propositional logic. A proof this result is beyond the scope of the course but it depends on using the law of the excluded middle (or reductio ad absurdum as they are equivalent. One approach is to break it into a giant collection of cases coming from $A \lor \neg A$ for each variable $A$.)

Theorems in mathematics ideally should provide deeper understanding and new tools to address old questions. One question we haven’t really broached but it immediate: how do I know when it is impossible to prove $Y$ with assumptions $X$?

Going straight from the defintion of a natural deduction proof, we would have to test all possible combinations of introduction/elimination rules. Not great.

However, from soundness, if we can find a single truth assignment with $X \mapsto T$ but $Y \mapsto F$, then we can immediately conclude that $X \not \vdash Y$, ie that it is impossible to prove $Y$ from $X$.

Example. Let’s show that we cannot prove $\neg A \land B \to C$ from $A \to B, \neg C$.

Let’s take $A \mapsto F, B \to T$, and $C \to F$. Then \(A \to B, \neg C \mapsto T\) while \(\neg A \land B \to C \mapsto F\) If we had $A \to B, C \vdash \neg A \land B \to C$, then from the theorem above we could conclude that $A \to B, C \vdash \neg A \land B \to C$.

We have arrived now at an absurdity. Our calculation shows that $X \not \models Y$ but our argument shows that $X \models Y$. We might be worried for second but then we remember the argument started out with an assumption: that we had a proof! The only way to avoid the absurdity for there not be a proof.

In this example, you can see the basic moves in propositional logic being employed in a real-life mathematical example.